Christmas: The Gift of Human Imagination

I don’t want to rain on Santa’s parade but as the days to Christmas grow short, we owe it to ourselves to take stock of the myths of the season and remember that the stories we sing and marvel at, all of the stories, are born of human imagination.

Even the most ardent believer must admit that the holiday today is an awkward amalgam of biblical tales and folk tales.

Jesus may be the reason for the season (our earth’s axial tilt notwithstanding) but his “birthday” is descended from the ancient pagan Roman solstitial Saturnalia: a week-long festival to honour the god Saturn. December 25th was chosen by the church in the 4th century to hijack Saturnalia in the campaign to consolidate Christian power.

On the night a Saviour is said to have been born, we layer on the folk tale of a funny fat man driving a herd of reindeer through the stratosphere who squeezes down chimneys. Not unlike the biblical Deity, he has hovered over us all year long, knows our thoughts and deeds and has decided if we are worthy of reward.

Okay, but it’s all about the virgin Mary and her baby boy, you say. Where did this idea come from? The first evidence of Christianity comes from letters from St. Paul decades after Jesus died. He didn’t mention the life of Jesus other than what he had picked up from others that “God sent his son” who was “born of a woman” (Galatians 4:4) and that “Christ died for our sins” (1 Corinthians 15:3-4). No notion that a human male was absent in Jesus’ conception. In his letter to the Romans, Paul notes that the “son of God” was “descended from David according to the flesh.”. Since Joseph was the descendent from David, Paul seems to assume that Jesus was born of Mary and Joseph.

So where did the idea of Jesus’ virginal conception begin? In only two of the four gospels, and nowhere else in the New Testament, do we read about the birth of Jesus. In Luke’s nativity story, Jesus’ parents lived in Nazareth in the north of Galilee. A Roman census forces the family back to its ancestral city of Bethlehem in the south of Galilee near Jerusalem. While they are there, Jesus is born. No empire-wide census was ordered and even if there had been, a Roman official world not likely order people to be counted in places their ancestors left years before. Besides, no census could have happened when “Quirinius was the governor of Syria” as Luke suggests, if Jesus was born when Herod was king. Quirinius did not become governor until 10 years after Herod’s death. So why did the author of Luke want to have Jesus of Nazareth born in David’s city? To fulfil the Old Testament prophecy of Micah that the saviour would come from Bethlehem (Micah 5:2).

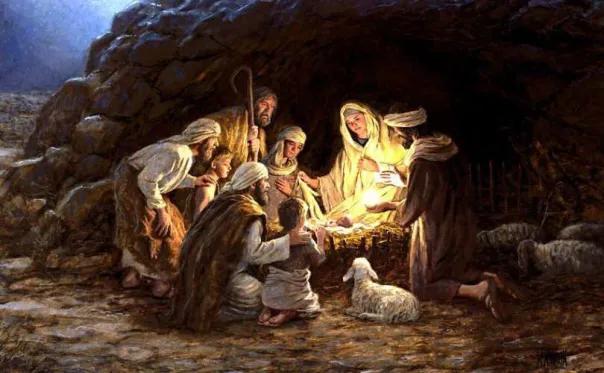

In Luke’s story, Mary and Joseph take Jesus home to Nazareth (2:39-40) but Matthew writes that they migrated first to Egypt to escape Herod’s wrath (2:13-14). Each account offers a different geneology for Jesus. Since these two nativity stories from Luke and Matthew don’t line up, we have amalgamated them to create our Christmas crèche.

One final point on the virgin birth, if you wanted to beef up an ancient mythology, a common polemical device was divine conception. That way, your heroic figure was more worthy of awe and worship. Life in the first century was rife with notions of virgin births and resurrections, fire-breathing prophets and liberating messiahs. Consider the close similarities, between Osiris and Horus in Egyptian mythology and the Christ of the gospels. Horus, the divine son, “left the courts of heaven” and descended to Earth. He was born of a virgin, became a substitute for humanity, went down to Hades to bring life to the dead, the “first fruits” to lead the resurrected into the life to come.

I mention all this not to be a literary Grinch. Heavens, I love Christmas. But I get more choked up by the conversion of Ebeneezer Scrooge than the appearance of angels and shepherds.

Admitting that the story of the birth of Jesus is just a story does not mean we should forfeit Christmas. Creches and haloes can delight us as much as Tiny Tim, Rudolph and Frosty et al. If we didn’t have Christmas, we’d invent something like it to bring light and love enough to get us through the cold dark winter.

And besides, as I say every year, I love mincemeat tarts.

Post a comment